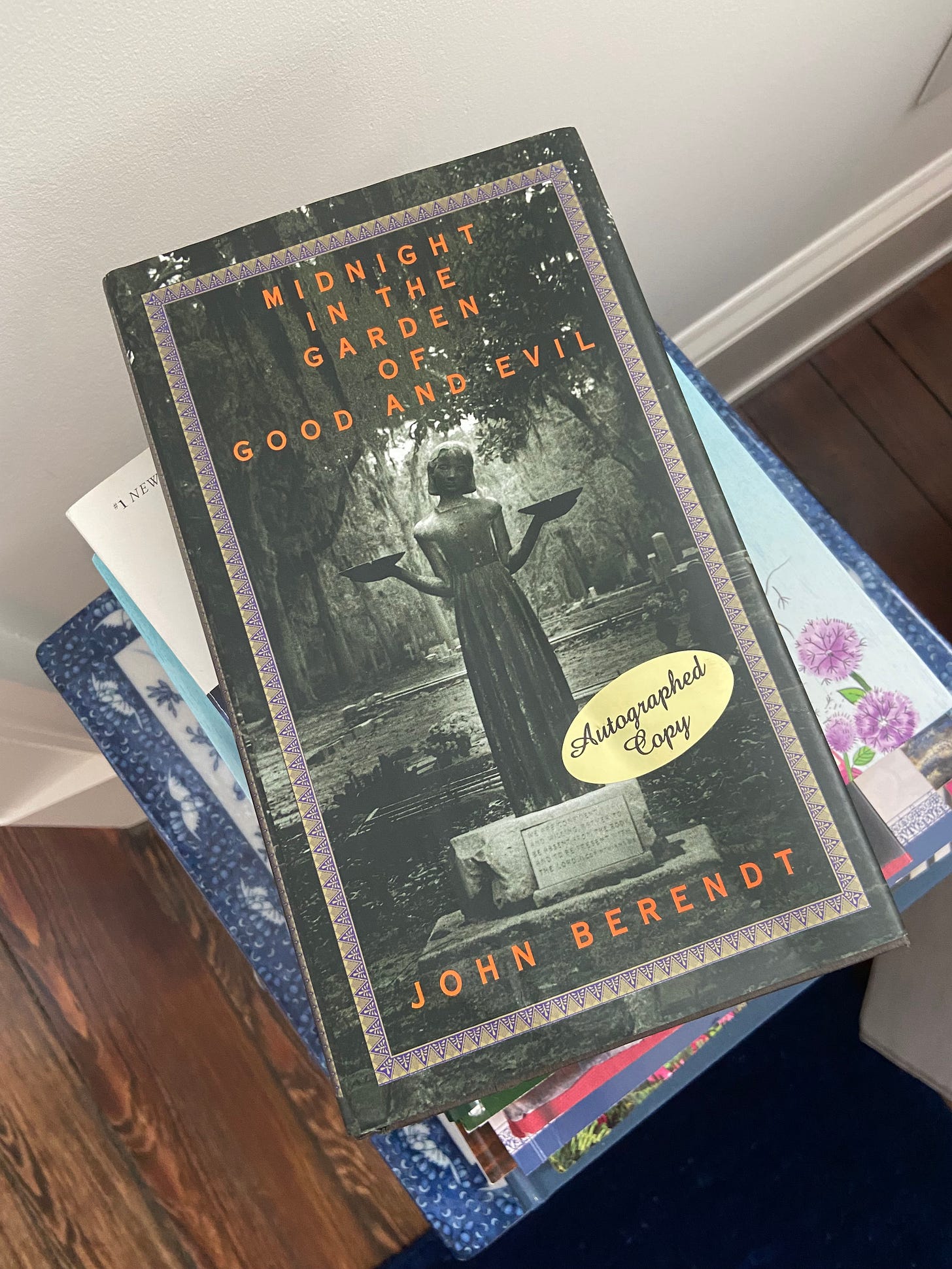

See last week’s post for Part 1 of my journey revisiting the book and film versions of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. Today’s newsletter is the story of my journey visiting Jim Williams’s house on the very first true crime tour I have ever taken!

On the second day of our Savannah vacation, we filled up our to-go cups and headed to Monterey Square to lay eyes on the Mercer-Williams House.

The first surprise is, you enter through the carriage house gift shop, which is full of . . . home decor and women’s wear?1 It’s actually a good preview of the tour itself, which is much more focused on the history of the home in the context of Jim Williams’s restoration prowess and eclectic taste in antiques than the crime. I wonder how the tenor of the tour has changed over the years, from the height of the popularity of the book and film in the mid- to late-90s to now, where of our tour group of four, two of us had comprehensive familiarity with the case and opinions, one had heard of it vaguely but wondered aloud whether Williams was still alive, and one had gotten a crash course in Midnightania over lunch at Zunzi’s.2

The tour begins in the first floor hallway, where the central piece is a (gorgeous) modern sculpture entitled The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Ominous! We moved through the dining room, exquisitely set with Wedgwood glassware and featuring a rare portrait of a man of color in aristocratic garb. One thinks Williams would have enjoyed Bridgerton.

After moving past the boudoir-red powder room and gorgeous spiral staircase that leads up to the family quarters (Williams’s nieces still own the house and one currently lives there), we entered what the tour guide called the “Blue Room,” but will be instantly recognizable to Midnight buffs as the scene of the crime. This is where my jaw dropped.

The room is SMALL. Much smaller than the set on which the incident was filmed, and the desk Williams was sitting behind when he shot Danny Hansford was positioned in the middle of this already, did I mention, s.m.a.l.l. room. I realized standing there that the distance between the two men during the altercation, especially if anyone’s arm was extended holding a gun, couldn’t have been more than two feet. What this means for Williams’s claim that Danny fired first and missed, or for the defense’s claim that the bullet hole in Hansford’s back came from the force of the first bullet spinning him around should be left to experts, i.e., not me. I will say that it increased my comprehension of the intimacy and intensity of whatever happened in that room that night.3

This room is also where the most content on the crime and trials is delivered. The company line is rigorously and vigorously pro-Williams, with any comments made about the case while in the house4 hewing to a “when he got a fair trial, he was exonerated” account, which unavoidably villainizes the victim: Danny was hired as an antiquing apprentice (and as our guide put it, “just so you know,” they had a “romantic relationship”); Hansford was “drugged out” and “crazy” that night; Jim killed him in self-defense. The End. The rest of the time in the room was spent talking about the displayed art, particularly a framed painting of a pair of courtly-looking legs. Apparently, when walls of stately homes got smaller, many portraits of nobility were cut in half to fit, and Jim collected and framed the legs. It’s endearing!

The remainder of the tour continues this personalization project. The final rooms we toured were parlors for entertaining5 and Jim’s “man cave,” prominently featuring a framed photo of him and his adored cat Sheldon (who had charmingly scratched the furniture). In many ways, the official tour is a restoration project of Jim Williams the man. You get a real sense of who he was, his sense of humor, his excellent taste. Needless to say, you don’t get that same sense of Danny’s humanity. All the rough edges and lingering questions of Berendt’s account are carefully sanded away like one of Jim’s handmade pieces of furniture.

We finished the tour back in the carriage house gift shop. It was then, with a question about why such an upstanding citizen couldn’t get a fair trial in Savannah, that the tour guide opened up. In a reveal so elegantly timed, and delivered with such a patented mixture of manners, empathy, and genuine sincerity that it was as if my beloved Southern stepmother had returned from the grave to deliver the line, our guide gently disclosed, “I knew Jim Williams.”

It turns out she had also met Danny Hansford, and was frank about her affection for the former and distaste for the latter. She was friendly with Williams for five years before the shooting, and said she encountered Danny once in the house and was “creeped out” by him. She also said Williams was not completely embraced socially because he wasn’t “from here,” he was new money, and he did not care to play genteel politics with the community. Interestingly, she was much more straightforward and unapologetic about his homosexuality than the book is, or than Williams was on the stand.6 She said he had several partners and no one really had a problem with it: it was Jim’s arrogance, not his queerness, that rankled upper-crust Savannah.

I’m not sure how often she shares such personal accounts of Williams and his place in the community, but those moments in the gift shop were revelatory for me, not because they disclosed any new secret knowledge about the crime (even in this informal convo, the guide’s take was firmly “this is what Jim said happened and I believe him”), but because it gave me a real insight into the way that one violent incident in a community can produce a proliferation of explanatory, accusatory, and exculpatory stories. There’s a new true crime narrative created about Danny Hansford’s death every time this tour is given, and who’s to say the one I heard on that steamy Saturday afternoon was any more subjective, biased, or incomplete than Berendt’s? Taking the tour reaffirmed and reframed my personal position on true crime scholarship and texts: they don’t exist to reveal the truth (or punish the perpetrator). Their social and cultural value is to use crime to explore and expose the way multiple and intersecting political realities shape both particular crimes and how we process them individually and culturally. As for the tour? Five stars.

To be fair, just about every commercial space in Savannah is full of home decor and women’s wear. The 24-hour gas station across the street from our hotel had enough flowy, floral-printed couture to outfit a slew of of coastal grandmas. And the last thing I wanted to see was merch that referenced the crime in any way.

A chain but highly recommended. Try the vegan meatball hero!

Another choice made by the film, to have Williams collapse from his fatal heart attack in the same room, positioned adjacent to where Hansford’s body lay (in some sort of clumsy visual statement about justice or fate?), is rendered impossible by the square footage. There is no space for two adult bodies in front of the desk. As our guide noted, Williams died at his front door on the way to get the morning paper.

Our tour guide was a bit more candid in an informal q&a back in the gift shop. Stay tuned!

The infamous Christmas party!

Where he did not describe his relationship with Danny as “romantic.” Instead, he claimed, “He had his girlfriend, I had mine. . . . We’d had sex a few times. Didn’t bother me. Didn’t bother him. I had my girlfriend, and he had his. It was just an occasional, natural thing that happened.”