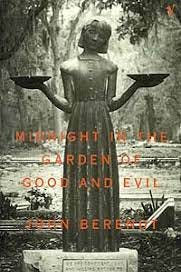

This newsletter comes to you from sultry1 Savannah, Georgia, where I’m enjoying the last days of summer before jury duty2 and course prep eat my August. While planning this trip, I thought it the perfect time to revisit another of the true crime texts that shaped my earliest academic interest in the genre, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.

Published in 1994,3 the book was instantly a huge hit. It begins when journalist and New Yorker John Berendt decides somewhat randomly to begin spending his free time in Savannah (must be nice), and he takes the first ten chapters to describe the history of the town, along with its eccentric inhabitants, at a deliciously leisurely pace. The first half of the book reads more like a biography of the city than true crime, with “the Yankee” recording his bemused and bewildered reactions to the Southern gothic types he encounters.4 When one of those types—antiques dealer, new money mid-Georgia transplant, and semi-closeted gay man Jim Williams—shoots his twenty-year-old lover and employee dead in his elegantly appointed historic mansion late one night, the book transforms into true crime.

The second half of the book closely tracks Williams’s four (!) trials, and for all the forays into hoodoo, Married Women’s Card Clubs, and University of Georgia football culture, it also includes a good bit of procedural meat, tracing instances of prosecutorial misconduct, forensic geekery, and the labyrinthine appeals process. This section covers years of legal maneuverings, and its conclusion, which I guess I won’t spoil (?) here, is truly surprising. The structure of the book, seducing the reader into slowly marinating in Savannahian culture and mythology until the gunshots that kill Danny Hansford abruptly and shockingly interrupt the narrative, models the best kind of place-centered true crime.

Though I was mostly delighted to revisit Berendt’s account, there were 1994 authorial choices that I bumped on in 2023. White residents are quoted describing Black neighborhoods as “slums” without context or criticism. The n-word and an anti-gay slur also appear liberally and unedited in quotations from non-Black and straight locals (often, the same non-Black and straight local). These unfortunate missteps are wisely excised in Clint Eastwood’s 1997 film adaptation, but a few others are regrettably introduced.

The first thought you might have is, was Clint Eastwood, native Californian, really the best director to adapt a story that is inextricable from its Lowcountry setting? The answer is no. What I wouldn’t give for a Barry Jenkins, David Gordon Green, or Callie Khouri adaptation of this text. But this is what we have, and there are issues:

Pacing

Rather than cinematically duplicating the book’s slow burn, Eastwood shifts the shooting to the night the Berendt stand-in, John Kelso (John Cusack), arrives in town. So all of the careful work the book does to make the city more than merely the setting for a crime is lost.

Authenticity

Berendt’s attentive detailing of the ins and outs of Williams’s years-long case is collapsed into one trial, and the film’s misguided impulse to cast Kelso as a traditional leading man (rather than the outside observer position Berendt inhabits) leads to a truly ridiculous moment where Kelso becomes part of the evidence introduced to exculpate Williams. In lesser, but no less irritating, deviations, Eastwood amplifies the eccentricities of the townspeople to a parodic degree: for example, mutating the inside joke of William Glover walking a long-dead dog from casual and knowing mentions of an invisible “Patrick” to the silly image of a man holding a gag leash every time he is glimpsed in the film.

Characterization

John Lee Hancock’s script shoehorns Kelso’s character into an underdeveloped and unconvincing flirtation with Savannahian Mandy, a choice that rankles me because there is truly no reason for a romance plot, and it has the added annoyance of forcing a character based on Berendt into a heteronormative relationship.5 Also, Eastwood cast his daughter in this role, which could otherwise be a 90’s nepo baby inevitability, but book Mandy describes herself as a “BBW” (Big Beautiful Woman), and Alison Eastwood is thin. So.

What’s more, there is the considerable and unavoidable ick factor that comes with seeing Kevin Spacey (as Jim Williams), who has been accused of multiple instances of sexual misconduct. Avoiding the film for this reason alone is understandable.

However, I want to close with one aspect of the movie that remains relevant and compelling: the performance of The Lady Chablis (as herself). Chablis (The Lady, The Doll), a trans woman, Savannahian performer, and unforgettable personality, has a prominent and indelible place in the book. She is the sole focus of the chapter entitled “The Grand Empress of Savannah,” in which she discloses her gender identity to Berendt with little shock or fanfare, and is referred to by feminine pronouns throughout. Chablis campaigned to play herself in the film, and listening to her is one of the (few) good choices the movie made. Tre’vell Anderson, in their history of Black trans visibility in pop culture, describes her role and its legacy as complicated but valuable:

We consider Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil a largely positive image of trans representation on film, and that makes sense; Chablis played a version of herself, a character who is allowed to, though not without pushback, assert her truth and evades the life-ending trauma and violence that often comes to Black trans folks in popular culture. But the transness of the character is largely subtext, a collection of whispers and comedic innuendos that we’ve ascribed a trans identity to because of the in-real-life ways The Lady Chablis carried herself.

Despite the shortcomings of the book and the film, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil remains an important mid-90s touchstone for marking the way the genre was pushing back against the dominant strain of authoritative true crime texts like In Cold Blood to produce more expansive and complex narratives of how violence reverberates through communities, and the shortcomings and blind spots of the criminal justice system.

Watch this space next week for Part 2, in which I tour the Mercer-Williams House, see something that changed my entire perspective on the story, and bought a fun dress (?) at the gift shop!

A more genteel descriptor than “sweaty,” though less accurate.

My consideration of whether a nearly thirty-year-old book counts as a “new” anything was interrupted by a profound existential crisis triggered by the realization that the mid-90s were nearly thirty years ago.

These portraits don’t read as condescending or voyeuristic as they could, and do, in other examples of northern creators engaging with the South (I’m looking at you Sweet Home Alabama, Low Country: The Murdaugh Dynasty, the collected works of Nicholas Charles Sparks, and even parts of the Paradise Lost trilogy), and are more a reminder that exceptional and contemporary Southern gothic texts like The Righteous Gemstones are not exaggerating much at all.

Berendt, as far as I can tell, does not comment publicly on his sexuality, though The Advocate defines him as “openly gay.” For what it’s worth, Berendt seems to have done the same thing to Joe Odom, a character in the book who is Mandy’s love interest throughout, but who is, according to the woman upon whom Mandy is based, queer.