Is it a crime to RushTok?

"Bama Rush" wasn’t a true crime documentary but maybe it should have been

Within the past week or so, two of my favorite cultural critics published pieces on Bama Rush, particularly its collateral online phenomenon, RushTok.

Anne Helen Petersen, right here on her outstanding Substack Culture Study, took us on a deep dive into the visual and colloquial vocabulary of RushTok, explaining how the University of Alabama students who tag their TikTok videos with the RushTok hashtag use the platform to document their experience “rushing” to join one of the university’s twenty-four sororities. The videos feature meticulously planned outfits, choreographed dance numbers, and girls who look frighteningly similar,1 but they carefully exclude mention of the prohibited “3 Bs” (booze, bars, and boys2). As Petersen notes, what the girls don’t say is often as important as what they do—appearing too eager, too gauche, or too queer3 can spell certain doom (no offers to join, or “bids,” at all).

Maybe it’s just something in the air,4 but sociologist and essayist Tressie McMillan Cottom published an op-ed in The Times this week about Bama Rush as well. Her piece digs even deeper into the racial/ist politics of RushTok: how the overwhelming whiteness of the girls demonstrates how little progress has been made in the American South in terms of social diversity and authentic integration; how little interest most Southern institutions have in addressing or even recognizing this problem; and how it contributes to unjust power dynamics long after graduation.

So, you might be asking yourself, why am I reading about sorority rush in a newsletter that talks about true crime and crime fiction? Good question! I found my way into this discourse through a brief phrase that caught my eye in Cottom’s essay. She writes

My friends who love true-crime podcasts were excited for the documentary from Rachel Fleit, “Bama Rush,” that was released on Max earlier this year.

Aha, I said to myself, I love true-crime podcasts, and I saw Fleit’s documentary a few months ago! What is the true crime connection?

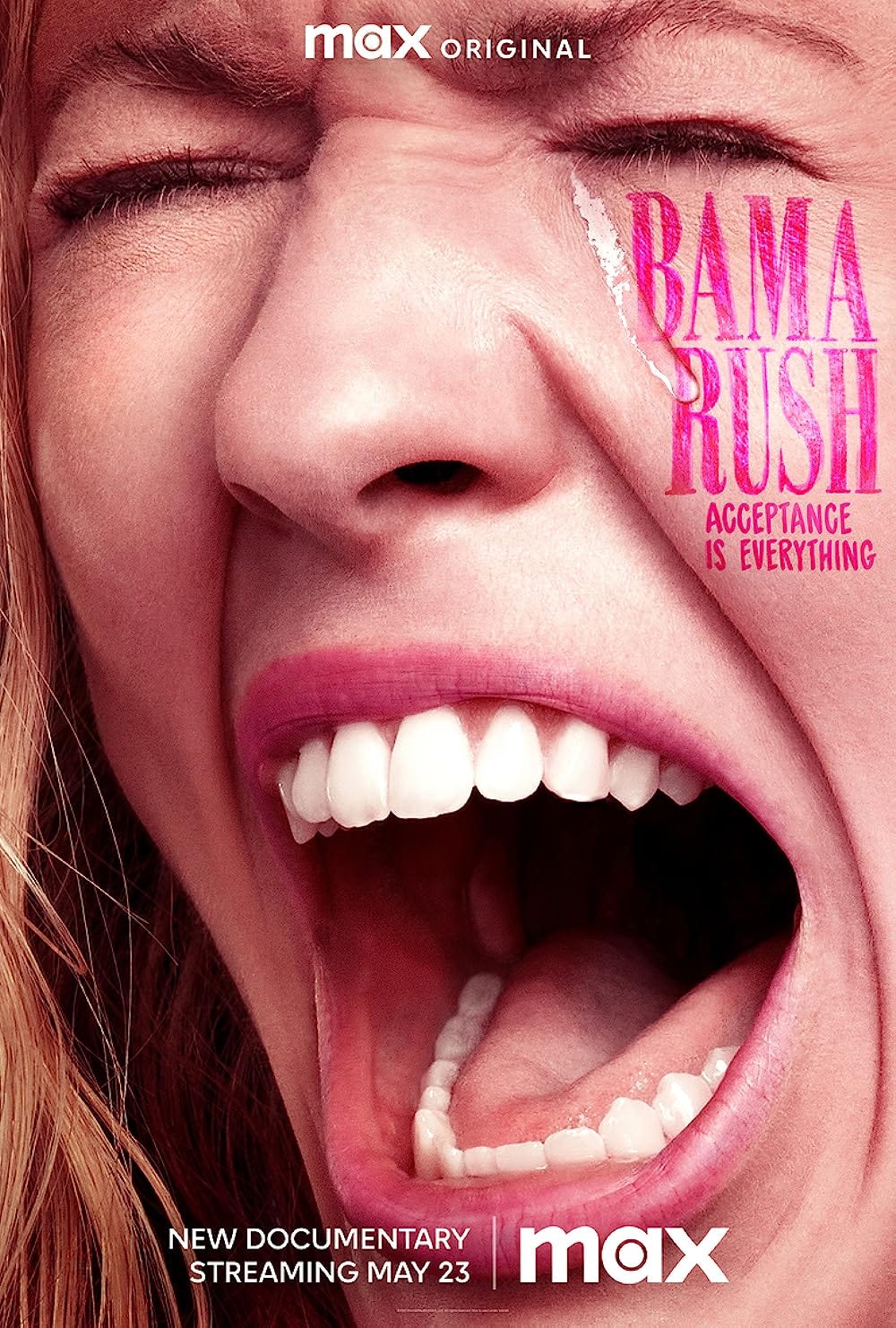

Reader, I couldn’t find one. Fleit has directed films on Selma Blair and a pair of trans cinematographers, but I could find no connection between the writer/director and true crime (or podcasts). However, Cottom’s comment made me think anew about Bama Rush, and the issues I had with it.

The film came across my radar not because of true crime, but because it was getting REAMED on Twitter.5 I won’t include the tweets here because they’re just so mean, but they all centered on Fleit’s decision in the documentary to center, alongside the stories of four girls participating in Bama Rush, her own struggles with alopecia. I am not one to comment on what it’s like to live with that condition, but I can tell you that the way in which Fleit includes the personal material does not work structurally or stylistically. The first mention is abrupt and disorienting, and it only gets worse from there.6 The real problem with Fleit’s choice is not discussing alopecia. It’s the way that focus crowds out real engagement with the girls and how they are framing their own experiences not only with Bama Rush, but also as young women navigating gender and sexual politics within this subculture.

Much like Petersen’s analysis of how the Rush code prohibits as much as it encourages, what is left out of Fleit’s documentary is shocking both in terms of content and her disinterest in following threads that if not technically criminal, are disturbing and dangerous. Here are a few elements Fleit neglected that had me giving major side eye to the screen.

Want to hire me as your rush consultant?

You totally shouldn’t! I am unqualified and uninformed.7 But apparently there’s nothing stopping me from offering my services to young women and their families for large sums. The rush consultants mentioned by Petersen and interviewed by Fleit seem to have no regulatory oversight accounting for the thousands of dollars potential new members pay them to consult on everything from hair to jewelry to social media scrubs. It would be easy enough to check whether a consultant in fact even pledged a sorority, but other metrics of success seem nebulous at best. For example, if, as Petersen convincingly argues, any rush consultant worth her David Yurman bracelets would advise a client to stay off of RushTok, why did so many of them appear on camera for Fleit? If not rising to the level of actionable fraud, this whole hustle seems highly shady to me.

RICO U

Thanks to recent events, we’ve all gotten a crash course in the complex of laws that target criminal enterprises. I wonder if some of those corrupt organizations have more than a little in common with the, brace yourself here, SECRET SOCIETY THAT RUNS THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA STUDENT GOVERNMENT called, you’re still not ready for this, THE MACHINE.8 As Cottom notes, the society isn’t all that good at staying secret if everyone seems to know about it, but that’s part of the point. It derives its power from the influence it (unevenly) peddles amongst sorority and fraternity members, positioning them for advancement in the corporate world. Fleit’s film references the Machine in the context of its potential impact on the film itself, but doesn’t follow through or follow up on either the nefarious innerworkings of the group, or its outsized impact in keeping not just the Greek system, but the entire university, almost exclusively serving the interests of rich white kids. Again, maybe not illegal, but extremely sus and worthy of some investigation.

The worst one

cw: mention of sexual assault

The most chilling moments in Fleit’s doc come when two of the subjects discuss their experiences with sexual assault. One rushee tearfully reveals she was sexually assaulted two weeks before school started. She conceptualizes rush and her college career as a way to rebuild her life surrounded by strong women who have also gone through challenges. Do sororities, or rush culture, actually help girls to do this? How? For everyone? The documentary moves on to more content about the controversy swirling around the filming itself rather than ponder these important questions.

Even more disturbing is a talking head interview where one of the subjects casually reveals that not only was she drugged at a bar the night before and found in the woods, it is not even the first time this has happened to her. Another of the documentary’s subjects was taken to the hospital that night where drugs were found in her system. She notes that the perpetrator was found using video footage from the bar and got “beat up real bad.” She declined to press charges because she didn’t want to go through the legal process “again,” having been roofied “three times before.” The girl’s seemingly untroubled affect while discussing this criminal drink spiking is not a reason to assume she is at all okay with what has happened to her, but the unfazed response of the film (and the filmmaker) is unconscionable. If she didn’t want to discuss the drugging it shouldn’t have been in the documentary at all, so including it without giving ample time to considering the ramifications on the young woman, as well as the misogynistic environment that makes such incidents alarmingly common and difficult to prosecute whether one is rushing or not, is for me a catastrophic failure of the film.

As Petersen and Cottom demonstrated this week, the traditions and trends that might seem frivolous or superficial (especially if they’re only read this way because women overwhelmingly participate in them) are often, to borrow a term from Petersen, rich texts that reveal valuable insight into our cultural priorities and prejudices. I think Fleit missed a huge opportunity to further our understanding of a slice twenty-first-century young womanhood in order to include material that might be personally relevant and significant, but that ends up underserving and diluting the voices of the girls the film purports to care about.

Thin, blonde, white

Think two of those Bs seem pretty darn similar? Me too! FWIW, Fleit’s doc shows a consultant warning against a full 5 Bs, adding Bible (religion), Bucks (money), and, lol, Biden.

Petersen’s 2017 study on celebrity culture, Too Fat, Too Slutty, Too Loud makes her an excellent thinker to take this topic on.

It is, shudder, “back to school time” now that I think of it.

Since it was called Twitter when these tweets were posted, that’s what I’ll call it here. Another weird house style challenge! Thanks, Elon!

I am holding back here, but if this newsletter ever goes paid, what will live behind the paywall is my snarky comments on bad documentaries like this one.

You’ll be shocked, shocked, to hear I didn’t rush a sorority in high school (it’s a thing) or college.

I am more than ready to buy any and all dark academia novels that address this goofy yet ominous operation.