It’s September! Time to sharpen pencils, organize Trapper Keepers, and cover textbooks with thick brown paper. Oh wait a minute, we’re not going to school in the ‘80s anymore! None of my first-year English composition students are going to be doing any of that. Instead, I fear, at least some of them will be entering my writing prompts and essay assignments into the generative AI1 engine of their choice and calling it a semester.

The rise of ChatGPT in the classroom has been swift and terrible, and the technology is also making its way into true crime texts. I wrote about its problematic use in What Jennifer Did a few months ago, and it turned up again in another docuseries I watched recently: Dirty Pop: The Boy Band Scam on Netflix.2 In this instance, the creators’ use of AI was disclosed early and often, but it still stuck in my craw.

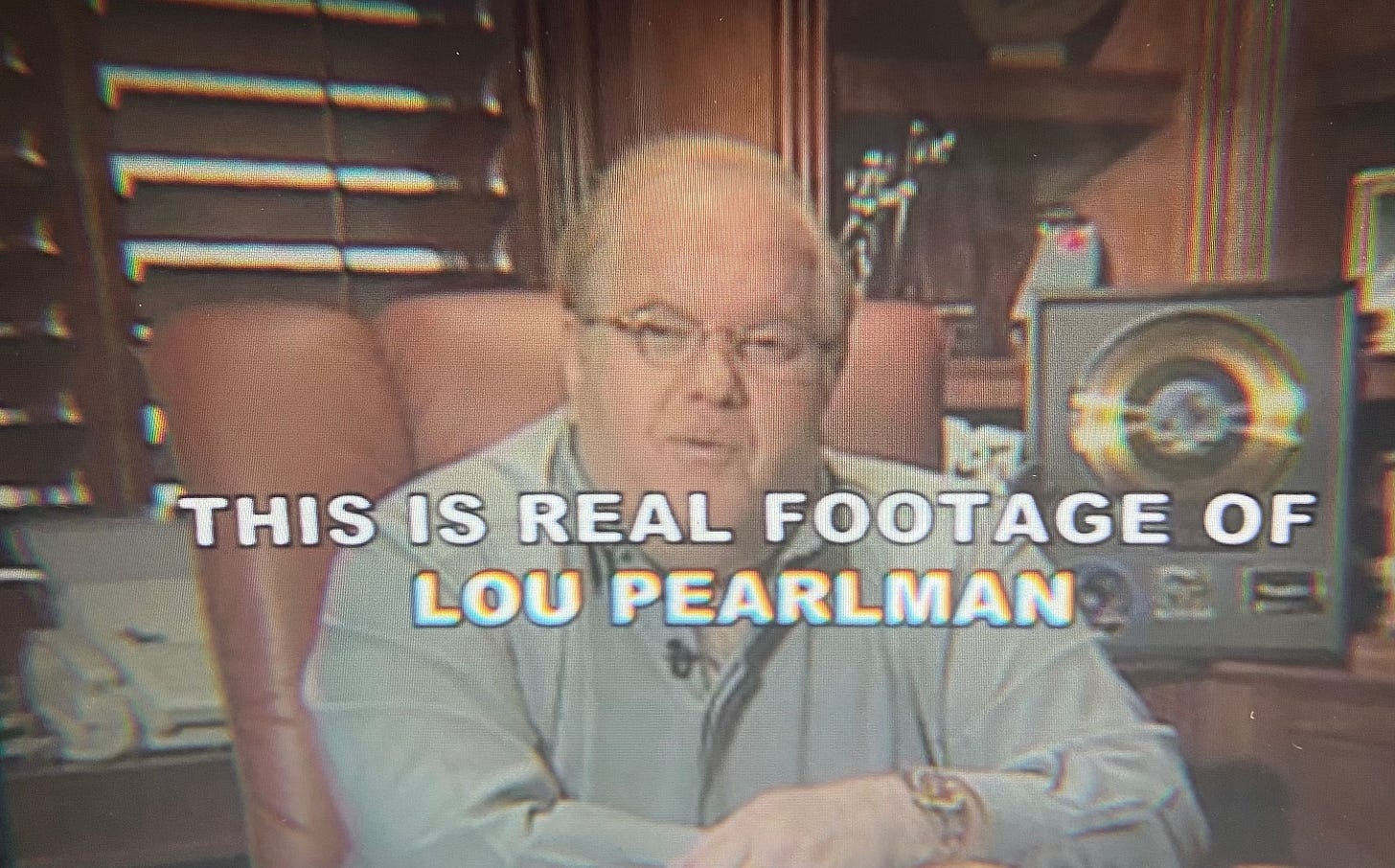

Before the first appearance of an AI generated Lou Pearlman (the talent manager and Svengali of boy bands like ‘NSync, Backstreet Boys, and O-Town on whose breathtakingly audacious scams the documentary focuses), we get this assertion:

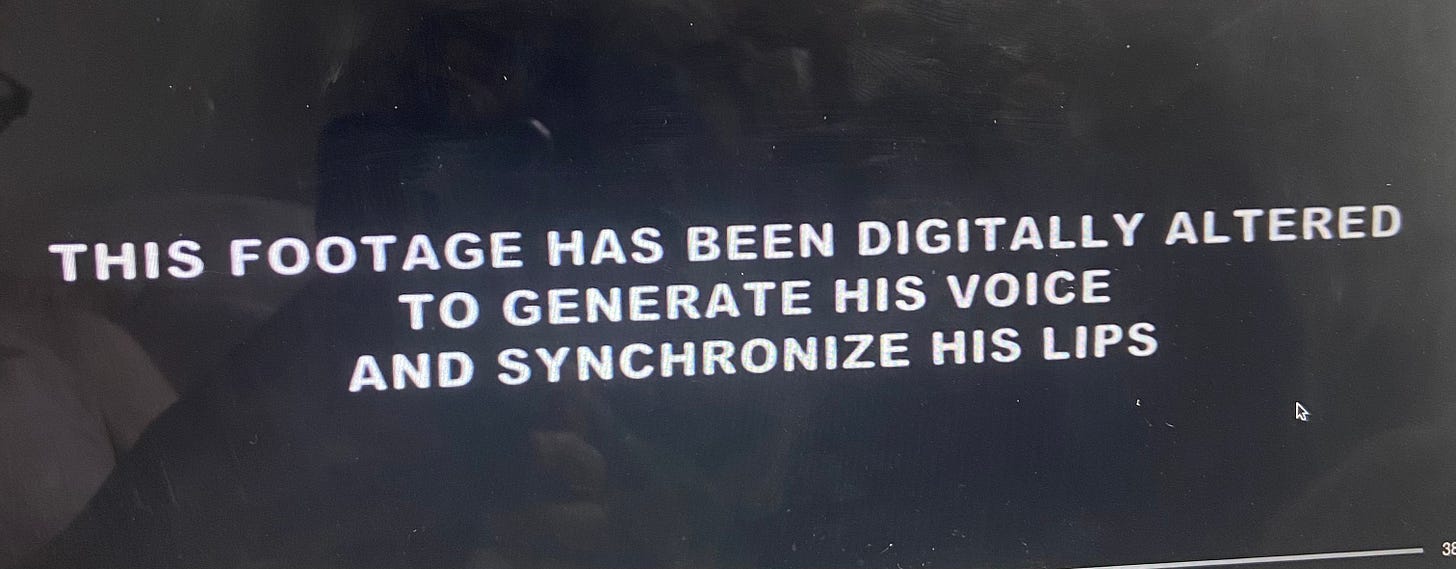

However, the commonly held definition of “real” to which I ascribe is about to be challenged with the next frame:

So “real” very explicitly does not mean “unaltered.” Apparently, “real” means “pre-existed in some recognizable form available for manipulation.” To be fair, and not to get too far into the weeds here, Errol Morris would absolutely concur that any image, and I suppose by extension any video footage, is never reliably “real” in the sense of an accurate reflection of external or objective reality. And I agree! This essay, and I am not exaggerating here, changed my life.

BUT. As much as I would like to imagine the producer and director of Dirty Pop are fans of ontological philosophy, I think we can all agree that they were not using AI in this instance to trouble our demarcations of the real. Rather, they wanted to have Lou Pearlman appear to be speaking words he wrote in his book, which were actually narrated by a voice actor. And my question is #why?

I think this use of AI is much less problematic than what they did in What Jennifer Did, which was generating photos to support an argument the film makes about an actual person’s life and personality. It matters that Pearlman wrote3 the stuff that Pearlman Bot appears to be saying in the doc. And crucially, the AI manipulation was disclosed in each episode of the docuseries. But what does it get us as the audience to see this? The point of including the excerpts from Pearlman’s book appears to be to highlight the ironic distance between how Pearlman saw himself (a savvy and empathetic businessman) and what he actually was (a fraudster who bilked millions out of investors, including his friends, to support a lavish lifestyle). But the only distance I could focus on was that between the interviews of actual band members and victims, which featured human beings speaking extemporaneously, and the strangely stilted and awkwardly framed segments with Pearlman Bot. It took me right out of the story.

In both of these instances, the use of generative AI distracts from what should be each film’s purpose: exploring and interrogating real crimes with real victims. A couple of weeks ago, I speculated on what new technologies might mean for how true crime stories get produced and consumed, and how we might define this era of true crime storytelling. I didn’t mention AI as a possibility, and maybe that’s because I’m afraid of what its use might mean for the genre.4

If we’re talking about AI, either exposing its use or debating its efficacy, we’re not talking about how these narratives are being framed and delivered in order to achieve justice, give victims space to articulate their experiences, interrogate and challenge cultural norms: any of the things I believe sophisticated true crime texts can achieve. Not to mention the fact that these chatbots are especially vulnerable to repeating and amplifying racial and gender bias, which is the last thing that true crime needs. I tell my students that using AI in their essays might seem easier, but it robs them of a chance to use their voice, and me of a chance to encounter it. I think I feel the same way about true crime.

At least according to a cursory Google (I’m part of the problem!) it seems we’re not including the periods to denote that AI is an abbreviation of artificial intelligence? Even that annoys me!

Full disclosure: this newsletter is not a review of Dirty Pop, but for what it’s worth, I thought it was pretty good.

He probably used a ghostwriter. But you know what I mean.

I’m not even getting into the truly terrifying implications of police officers using AI to write crime reports.